Grades of Quality of Panama Hats

Summary: There is no standardized grading system for Panama hats. Different sellers often use the same numbers or terms to describe very different hats.

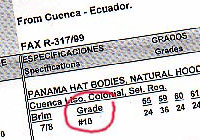

Many sellers use numbers to describe Panama hat “grades.” Unfortunately, they use different formulas to calculate their grade numbers. So a Grade 10 from Seller #1 is not the same quality as a Grade 10 from Seller #2, and both are different than a Grade 10 from Seller #3.

Many sellers use terms such as Fino Fino and Super Fino to describe Montecristi Panama hat “grades.” As with numeric hat “grades,” different sellers often use the same words to describe very different hats. Unfortunately, there are no Hat Grade Police.

The common practice of different sellers using the same numeric or word “hat grades” to describe very different hats is one explanation for why sometimes the words sound the same, but the prices are so different.

Conclusion: You cannot reliably compare hats from different sellers by comparing the “hat grade” numbers, or words, they use to describe their hats.

1. Introduction

Hat grades? Let’s make it simple. For all practical purposes, there is no such thing. Sure, everyone talks about them. They even seem to be using the same words, or the same numbers. But Panama hat “grades” are not like coin or stamp grades. With coins and stamps, there are industry-wide grading systems and standards. Different sellers use the same grade names, terms, and descriptions to mean the same things. But with Panama hats, anything goes. There are no industry-wide grading systems, no standards, no strong trade association, no regulatory body. Not surprisingly, there are many more sellers of “Super Fino” Montecristi hats than there are weavers of Super Fino Montecristi hats.

Sorting hats in Cuenca

2. Numeric Hat Grades

Summary: Many sellers use “hat grade” numbers to describe their hats. Disregard. Useless. Like comparing apples and oranges and aardvarks. Everyone uses a different “system.”

Using a branding iron to put the company mark in hats in Cuenca

First, let’s explore the numeric “hat grades.” A seller might say his hats are Grade 8. Or Grade 15/16. Or 30. Numeric hat grades are most often used to describe Panama hats woven in Cuenca (kwain-ka), Ecuador. They sound good, don’t they? Factual. Authoritative. Reassuring. Useless.

During the past 16 years, I have done business with the three largest hat exporters in Cuenca (Ortega, Dorfzaun, Serrano). They all use hat grade numbers that sound like they are all using the same system. But guess what? Each exporter has a different formula for deciding what grade a hat is. A Grade 10 from one company may be a Grade 14 from another and a Grade 12 from the third. They are all located within a couple of blocks of one another, and no two can agree on what grade a specific hat is.

If the exporters in Ecuador can’t agree on what grade a hat is, what do you think happens when the hats reach U.S. or European hat manufacturers and retailers? Right. The discrepancies and confusion are compounded.

The only context in which those grade numbers have any meaning is when you’re comparing numbers from the same seller. The same seller’s Grade 12 will be better than his Grade 8. His Grade 4 will be better than his Grade 2.

3. Word Hat Grades

Summary: Montecristi Panama hat “grades” are often expressed as Fino, Fino Fino, Super Fino. Some sellers make up their own “grades,” such as Ultrafino, or Museum Quality. Since the sellers all use the terms to mean whatever they want, these hat “grades” are useless to you, the consumer, as a way to compare hats from different sellers. Disregard all such hat “grade” terms.

Sadly, the same problems also apply to “grades” of Montecristi Panama hats. As stated earlier, there is no “official” grading system. There is no regulatory body. There are no Hat Grade Police. Each manufacturer or retailer or whatever wants to sell his merchandise. So he presents it in the best possible light. This sometimes may include overstating the quality. Imagine that. A seller overstating the quality of his/her product.

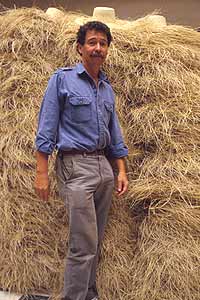

Your humble hat servant in Píle (near Montecristi)

Your humble hat servant in Cuenca

Rosendo Delgado’s sign in 1988

Montecristi Panama hat “grades” are often described as Fino, Fino Fino, Super Fino. In theory, those terms mean fine, very fine, super fine. In practice, they mean nothing. The problem is that those terms are totally subjective, a matter of personal opinion. What one boastful seller calls a Super Fino a more modest, or more honest, seller might call a Sub Fino. There are no written guidelines, such as: A Fino quality hat has 20 rows of weave per inch, a Fino Fino has 25 rows of weave per inch, and a Super Fino has 30. No rules.

I have seen ads and Internet listings for Montecristi Panamas that the sellers say are Super Finos, but the prices say no they’re not. I like to know what’s going on in the marketplace, so sometimes I order one of these suspiciously low priced “Super Finos.” So far, they have all been average, or below average, hats. But a real Super Fino should be an awesome hat. And priced accordingly. Obviously, the “system” of Fino, Fino Fino, Super Fino, etc. does not mean doodly squat in the real world marketplace.

Master Weaver in Píle

This guy must be the top banana

She has the biggest pair of papayas I’ve ever seen

Mona who?

Pretty Maids All in a Row

Think of it this way: anyone can write Super Fino in a couple of seconds. There are only 18 Master Weavers who could actually weave one, and it would take months to do it. It is much easier to write a high quality hat than to weave one. And cheaper. Comparing descriptions, or comparing words, is not at all the same as comparing the actual hats. The only truly reliable way to compare the quality of two hats is to examine them side by side.

I’ve seen a lot of listings on eBay for “Montecristi” Panama hats. Some of them are selling for under $20. Naturally, they are all “high quality” and “Super Finos,” even some “Ultrafinos.” Forget it. These hats contradict the first law of business—make a profit.

I have been buying my hats personally in Montecristi for more than 16 years. During that period, I have probably purchased more Montecristi hats than anyone else in the world. And I can tell you this—even an average quality Montecristi hat cannot be purchased for under $20. Not even if you are buying direct, in Montecristi. So if you can’t buy an average quality Montecristi for that price, you certainly can’t buy a “high quality” or “Super Fino” Montecristi for that price. These hats are probably decent hats, probably worth the prices charged. So if you want a low priced straw hat, go for it. But they are not very likely to be finely woven, cloth-like masterpieces created by one of the few remaining Master Weavers, then beautifully hand-blocked.

As a general rule, fine hats are not bargain priced. In fact, fine anything is rarely bargain priced.

Sometimes dealers make up their own grades, such as Artisan Quality, Connoisseur Quality, Collector Quality, or Museum Quality. I actually made up a similar system some years ago, coining the term “Museum Quality.” One of my clients liked it well enough to start using it himself. Interestingly, I decided against using that kind of “grade” system. Because what does any of that mean, really?

When I coined “Museum Quality,” I meant for that term to be used to describe a hat that was of such incredibly fine quality as to be worthy of putting in a museum, literally, as an example of the very highest level of the art of hat weaving. There are fewer than twenty hats woven each year that would be what I would call Museum Quality. So when I use the term “Museum Quality” I mean something different than someone else who might use the same term to mean hats priced higher than $750. It’s not a matter of Right or Wrong. It’s a matter of communication.

So whether sellers are describing their hats as Super Finos or “Museum Quality” or Platinum Quality or Grade 30 or whatever, none of it means a thing. Not really. Unless we all use the same terms to mean the same things, the terms have no meaning at all. Which is a better hat—one seller’s Super Fino, another seller’s Museum Quality, or a third seller’s Platinum Quality? How could you possibly know without actually seeing the hats and comparing them side by side? You can’t. You simply cannot compare hats by comparing the “hat grade” words or numbers used to describe them.

That is why I do not use any of the common “hat grade” terms to describe my hats. And why I decided not to use the naming system I made up myself to describe different levels of quality. It’s time to get rid of all of those meaningless “hat grades.” It’s time for a Panama hat grading system that really works. One that is easy to understand, that makes sense, that is more fact than opinion. And most important of all—it’s time for everyone to start using the same system.

4. Counting the Rings

Summary: Counting the rings inside the crown of a Panama hat is interesting and fun, but it is not a reliable way to judge the quality of the hat.

This is a finely woven Montecristi Panama hat turned inside out so you can see the rings.

You may have heard that you can judge the quality of a Panama hat by holding it up to the light and counting the number of rings visible on the inside of the crown.

Well, that works some of the time. Maybe even most of the time. But there are enough times that it doesn’t work, that I would recommend against using this as your primary way of judging quality.

I learned this the very first time I went to Montecristi and compared hats.

When I buy hats in Montecristi, I pay no attention whatsoever to how many rings they have. I look at the hats themselves, not at the rings.

That doesn’t mean you shouldn’t look at the rings in the crown. It’s interesting. Hold the hat up to a strong light and look at the inside of the crown. You’ll see the rings. You might even want to count them. I sometimes do. But don’t let the number of rings determine which hat you buy or how much you pay.

Of course, if you’re shopping on the Internet and you can’t look at the hats themselves, well, maybe it’s worth asking. For certain, a hat with three rings is not a fine quality hat. And a hat with twenty-seven rings probably is a finely woven hat.

A better way to judge the fineness of weave of a hat you can’t see is to ask the seller to count how many rows of weave there are per inch. I am working with The Montecristi Foundation to develop a comprehensive, objective grading system and nomenclature for determining the relative quality of Panama hats.

5. How To Measure Fineness

Summary: The best way to measure the fineness of a woven hat is to count the rows of weave per inch (or 2.5 centimeters), first horizontally then vertically.

“How finely woven is the hat?” is usually the first thing someone wants to know about a Panama hat. With most woven items (fine cottons, oriental rugs, etc.), quality is at least partly determined by how many strands per inch there are in the weave. The same is true of Panama hats.

The grading systems used by the exporters in Ecuador that give a number to describe the hat grade, such as Grade 10/11, are based upon counting the rows of weave per unit of measurement (usually a centimeter). But then they complicate it by taking the number of rows of weave actually counted and multiplying it by this and subtracting that and dividing by something else etc., until each of them ends up with a different number to describe the same hat.

Unfinished hat

Mother and daughter weaving

Call me dumb, but I don’t get it. Why not just count the rows of weave per unit of measurement and leave it at that? That would be easy enough to understand, and easy enough to repeat and verify yourself. If hat A has 12 rows of weave per inch, and hat B has 24 rows of weave per inch, then you know that hat B is more finely woven than hat A, even without being able to see either hat.

Of course, since the fineness of weave is never completely, exactly identical throughout the hat, one could search around on the hat to find a spot where the weave is finer than elsewhere on the hat. Even so, you still have more real information with “20 rows of weave per inch” than you would with “it’s a Fino Fino.” 20 rows of weave per inch is a fact. Fino Fino is an opinion.

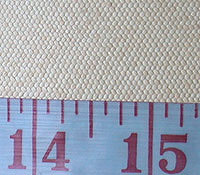

The Montecristi Foundation grading system begins with a single number called the Montecristi Cuenta.

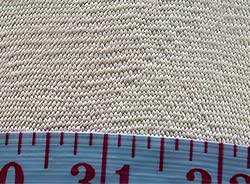

To determine the Montecristi Cuenta of a Panama hat, count the number of rows of weave in one inch horizontally (or 2.5 cm).

For the hat in the photo to the left, the horizontal count would be just a little under 23.

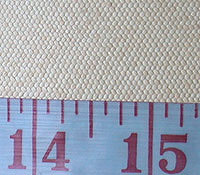

Then count the number of rows of weave in one inch vertically.

The second photo shows the vertical measure of the same hat in the same area of weave. The vertical count would be 27.

It is not unusual for the vertical and horizontal counts to be different. Actually, it’s unusual for them to be the same. Usually, the vertical count is a larger number.

Now multiply the two numbers together. 23 x 27 = 621. The number 621 would be what is called the Montecristi Cuenta for this particular hat.

This is a very finely woven hat. A hat with a Montecristi Cuenta over 900 is a rare treasure. A hat with a Montecristi Cuenta under 300 is not an especially noteworthy hat.

Did you try to count the rows of weave yourself? It’s not easy, is it? It’s hard even in the photo above where I digitally sharpened the lines and boosted the contrast; it’s harder to count when looking at the hat itself. Manually counting the rows of weave is a tedious task. In order for me to be able to do this with every single hat I have in inventory (over 2000 Montecristi hats), or when I am purchasing hats in Montecristi, I would need some sort of handheld scanner to speed up the process.

Counting the rows of weave with a hand lens is a tedious task.

The first person I met in Montecristi

If there are any inventors out there, the ideal scanner would be about the size of the handheld scanners I’ve seen used at the checkout register in some stores. The scanner would have a one inch by one inch reading window that would be placed against the surface of the hat. The user would push a button or pull a “trigger” and the scanner would scan the rows of weave both horizontally and vertically. The LED readout would report that the hat is 23-27-621.

Call me when you have my scanner ready.

In the meantime, I only do an actual count on the very fine, very expensive hats.

Determining the fineness may be the most important part of grading a hat. But there are still other important factors to be considered before making a final decision.

6. Other Grading Factors

Summary: In addition to fineness of weave, any system for grading Panama hats must also take into consideration the quality of the weave and the color of the straw because they are also factors in the overall desirability of the hat.

A fine hat in progress

While fineness of weave is certainly the most important factor when grading a Panama hat, you must also consider the quality of the weave. Is the hat well woven or poorly woven? Ah, but now we’re back to opinion. Fineness of weave is just math; you can count the rows. But quality of weave is very subjective. It’s easy to tell excellent from awful, but how does one decide if the quality of the weaving is excellent or just very good?

Judging the color of the straw is even more subjective than the quality of the weaving. The photo to the right shows five different Montecristi hat brims. Each is a different color. I have no objection to any of them. Is one color “better” than another? You might prefer one shade over another, but someone else might prefer a different one.

A hat that has an even color throughout is probably quite acceptable. A hat that has one area where the straw is obviously different than the rest of the hat is probably less desirable.

Different colors of straw

Straw drying near Montecristi

Almost every hat will have at least some red and/or gray straw. How many “points” would you deduct for that? Especially when you consider that many people prefer the subtle patterns that are often created by the slightly different color straw.

When I’m grading a hat, either to decide whether or not to buy it or what price to give it, I look at the whole hat for an overall impression of “desirability.” If most people would prefer one hat over another, then the preferred hat should get a higher grade than the less desirable hat.

7. How I Grade and Price Hats

Summary: First, I look at the hat for an overall impression of how visually appealing the hat is. Then I consider fineness, weave quality, and straw color.

Montecristi hats in Montecristi

When I am buying hats in Montecristi, I will examine a couple of hundred hats in a day. First, I give the hat a quick look for an overall impression. If the weave is obviously below my minimum fineness standard, or if the weave is horrendous, or if I spot a stain or an area of straw scarred by the apaleador, then I put that hat into the No pile.

Remember: ALL HATS HAVE SOME FLAWS, IMPERFECTIONS, AND IRREGULARITIES. If I bought only absolutely perfect hats, then I would never buy any hats.

Hats that are not rejected immediately are examined more closely. First, for fineness of weave. I have looked at so many Montecristi hats for so many years, that I can very quickly estimate the fineness of weave. I do not have to actually count the weave of each hat to determine its approximate fineness.

But Fineness is only one factor. It may be the most important factor. It is usually what people want to know about first. Even so, Fineness is still just one part of the total equation.

The hat we looked at above in section 5, for which we counted the weave, was 23 by 27, a finely woven hat. So, if I told you that another hat was 30 by 23, you would know that is even more finely woven than the first.

So then it should be worth more, right?

Apaleadores in Montecristi

Finely woven, but not well woven

Not necessarily. We need to see how well woven it is.

Look at the photo on the left. There is an area on this hat that counts 30 by 23. And overall it is a finely woven hat. But you can see easily that the rows of weave are not even close to being straight. The thickness of the individual straws varies significantly. There are irregularly woven areas that look very different from the surrounding weave. And many other very visible flaws.

Compare the weave above with the weave to the right. The hat above is more finely woven. But which hat would you prefer to own? I think most people would prefer the beautifully woven hat to the right over the more finely woven hat shown above.

To me, the hat above is so irregularly woven that its price should be significantly lower than the price of the hat to the right. Possibly as much as 3 or 4 price levels lower.

So when I price hats, I start with Fineness of Weave. I count, or estimate, the fineness and set a price based solely on that.

Next I look at the Quality of Weave. If the Quality of Weave is within what I consider to be an average range, then I stay with the price assigned to the hat based solely on fineness. If the Quality of Weave is significantly better than average, I would give the hat a +1, or possibly even a +2, meaning that I would raise the price by one or two levels. Conversely, if the Quality of Weave is significantly below average, then I would give the hat a -1, or possibly even a -2, meaning that I would lower the price by one or two levels.

When pricing the irregularly woven hat above, I gave it a -2 for Quality of Weave. The beautifully woven hat above right was given a +1 for quality of weave.

The third factor is Color of Straw. If the Color of Straw is exceptionally clear and even, then I would give the hat a +1. If the Color of Straw is a problem due to excessive amounts of gray or red straw, then I would give the hat a -1, possibly even a -2.

I am more likely to buy a hat with irregular weave than with color problems. To me, a finely woven hat is desirable even if there are irregularities in the weave. Generally, one has to look closely to see the irregularities. But a color problem is obvious and detracts immediately from the appeal of the hat.

So the combination of Fineness of Weave, Quality of Weave, and Color of Straw determines the price for the hat. The unblocked hat.

The other factor that affects the price of any particular hat is the shaping and finishing. It is more costly to shape a hat with high quality hand-blocking done in the US than with a hydraulic press in Ecuador, or in the US.

There are only 5, maybe 6, craftsmen in the US who can do high quality hand-blocking of Montecristi hats. (Naturally, I think my own hand-blocking is superior to any of the others.)

I have never seen a hat that was hand-blocked in Ecuador that came anywhere close to meeting my standards. Of course, I do admit to being an unrepentant perfectionist. Hats that have been hand-blocked in Ecuador may look fine to you. You may prefer lower cost over higher quality and superior aesthetic.

However, let’s say you could examine two hats side by side. The two hats are identical, except that one was hand-blocked and finished in Ecuador, and the other was hand-blocked and finished by me. I believe the differences would be immediately obvious to you.

See also Why One Hat Costs More than Another.

Finely woven, and well woven

The future of Montecristi hats is literally in her hands

Text and photos © 1988-2026, B. Brent Black. All rights reserved.

100% Secure Shopping