Ironing It Out

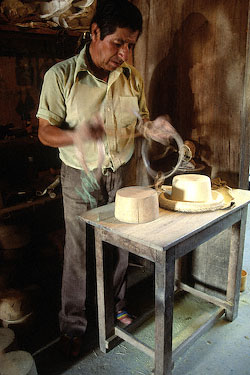

14. The Planchador Irons the Hats

Nestor Franco heated his irons by nestling them into hot coals.

He made his fire first thing each morning. While the fire burned the wood into coals, he readied his irons and gathered his other tools: wood forms, half-inch-wide leather belts, sulfur powder.

Nestor’s workshop reminded me of a tidy old garage with lots of interesting stuff in it. A good place to hang out.

There were usually one or two other artisans working for Nestor, and as often as not a kid or two watching and/or getting in the way.

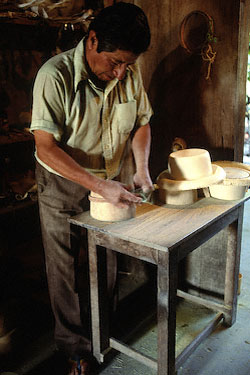

There’s Jose Chavez again, working with scissors.

The workshop opened onto the street in front, and an enclosed courtyard in back where hats could be spread out to dry in the sun, its equatorial intensity softened by a couple of palms and a jacaranda.

Below are some of the forms Nestor used to iron the hats. They are different sizes, different heights. Some are flat on top, others are round. Nestor had at least a hundred forms.

Montecristi Panama hats drying in the dappled sunlight of Nestor’s enclosed courtyard

Nestor pulled his hats over these wood forms,

pulled and belted them taut as a drum, then ironed the hats.

The wood forms are made of a completely different type of wood than are the apaleador mallets. Opposites. The wood for the macetas is extremely dense. The wood for the forms is very light, like balsa wood. The forms the weavers use are made of the same wood.

There is a good reason for the very light forms. When a hat is on the form, and three–year–old Danielito chases the family cat through the house, and the hat on the form hits the concrete floor with a sickening thunk—the light wood forms are less likely to damage the hat upon impact than a heavy wood form.

I once bought an entire tree of this light wood.

I wanted to have forms made for the weavers. Easier dicho than hecho. Just finding out what kind of wood to use was a challenge worthy of the CIA. Caco. Eventually, we were told by one of the hat dealers that the tree is called a caco tree. So we went out looking for caco wood.

Have you ever shopped for caco wood in Ecuador? It’s a lot like a North American snipe hunt. We tried lumberyards, furniture makers, wood workers, anyone we could think of and find. Finally, in our twenty-eighth try, and our third lumberyard, another customer overheard our request. After we were told, again, that there was no such tree or wood, the other customer caught my eye and signaled we should talk outside the lumberyard.

Tree intrigue. The life of a Panama hatter is weirder than you can possibly imagine. Well, this Panama hatter.

He gave us our first good lead: a name and a phone number.

Alicia (the interpreter from hell) called the number and asked about buying a caco tree. This was one of the times I was grateful to be able to hand the phone to someone else and plead poor Spanish skills. She arranged for us to meet with two strangers in a small town 30 kilometers from Montecristi. We were about to buy a caco tree.

Imagine you live in a very small town in rural Ecuador near the Pacific coast. You look up and here comes a gringo. I’m obvious. I don’t pass for local. (Come to think of it, I don’t pass for local anywhere.)

I approach, smiling, and tell you in fairly bad Spanish that I am looking for two men who are going to sell me a tree that I will use to make hats.

“Did you already give them the money for this tree?” was the usual response. (Translation: Just how stupid are you?)

We took a walking tour of the town, asking everyone who didn’t run away about Eduardo and Manuel and our caco tree. Chickens always ran. Children usually did not. Pigs were hard to predict. About the time the locals were thinking of calling a town meeting to decide what to do with us, Eduardo and Manuel showed up. It was a go. So we went.

We drove a short way out of town and pulled off the road. We hiked out into what looked like a pasture. They took me to a tree. They gestured at it enthusiastically and said that was my tree.

Tools of his trade. Wood form. Leather “belts.” Sulfur powder.

Nestor chooses a belt for the form.

Yikes. My tree is still “on the hoof” or on the root. It’s a live tree with leaves. Oh no. This is like choosing a live turkey or lobster. It seems too personal. I imagined logs or something, not a live tree. I’m a dyed-in-the-cellulose tree hugger from way back.

Okay, I’ve cut my own Christmas trees on tree farms in California and in the woods in Kentucky where I grew up, so this is like that. I avoided giving the tree a name, like Woody or Jose.

Okay. My tree. My caco tree. I tried to feel proud.

It was a nice enough tree. Not a big tree. About twenty-five feet tall.

“This is the kind, is it?”

Si.

How was I supposed to know? Or test? Can’t exactly heft a rooted tree in my hand to see how dense the wood is. Uh…deal.

I marked the tree to show them which branches to use and how far up each to cut.

Nestor tightens the belt around the form

The entire time I was doing this tree purchase thing I was conscious that I was way off the grid. I didn’t know who these guys were. I didn’t know whose field it was. I didn’t know who actually owned the tree. I didn’t know if it was a caco tree. I didn’t know if $40 was a fair price for a caco tree. For all I knew, these two hustlers might have already sold this same tree four times that month. Oh, those crazy gringos.

It worked out fine. Eduardo and Manuel delivered as promised. Eventually, I actually delivered several dozen forms to weavers.

That year, Diego and Jorge delivered about seventy forms (hormas) to weavers. We bought up all the caco wood the maker of the hormas had on hand. Then we gave him money to buy more caco wood to make more hormas. The forms were provided to weavers at no cost.

Some years later I created “libraries” of hormas which included sizes from 52cm to 63cm, and three different heights – 10.3, 10.8, and 11.3. One “library” is for hats woven in Las Pampas and the other is for hats woven in Pile. I decide what grades, sizes, and heights I want the weavers to weave, then we loan them the right form to weave each hat. When the hats are woven, we pay for them, and loan a new form to weave the next hat.

Nestor would choose a form to fit the general shape the weaver had woven. He would want the hat to fit very snugly onto the form. Sometimes he might try several forms of different sizes before finding the right one.

Nestor fits the form to the hat.

An unexpected face appears lower left.

Nestor Franco knew his stuff. He was a good apaleador, a great planchador. His family was famous for their ironing for several generations. None of Nestor’s children practices the family art. His brother did. Photos of Alvaro Franco are below.

When Nestor found the right form for the hat, he removed the hat from the form and put a half-inch-wide leather belt over the form. He tightened the belt on the form, without the hat. (right) He usually had to work to pull the tightened belt off the form.

Below left, he put the hat onto the form then put the tightened belt over the hat. He had pulled the belt as tight as he could before he tied it. By adding the thickness of the hat all around the form, the belt is tighter than ever.

He pulls the belt tight and ties it off.

He pulls the hat onto the form, then pushes the tightened belt over the hat.

He has put another form under the first and pulls the hat taut on the form.

Right, the belt does not fit. It will not go all the way to the bottom of the form. But it must go all the way to the bottom. Nestor wanted the belt to be impossibly tight so it could hold the hat in place as he pulled the hat onto the form like a coat of paint. He pulled the hat tight all around, then pushed the belt farther down. He pulled the hat again and pushed the belt down again. Sometimes he used a block of wood as a pushing tool.

Wiping the brim.

Rubbing sulfur powder into the weave.

Nestor often worked up a good sweat pulling hats onto blocks and belting them tight. When done properly, it is very hard work.

Nestor wiped each hat all over, rubbing sulfur powder into the weave, before he began the ironing.

Wiping the iron.

Ironing the crown (la copa).

Nestor wipes the wood ash off the hot iron. (left) A planchador who doesn’t know his ash from his elbow can be seriously burned.

Nestor always placed a piece of cloth or paper between the iron and the hat to protect the hat from scorching. (right) His strokes were long and rapid. He pressed hard. Ironing a hat is not like ironing permanent press pants. While ironing a hat, the planchador is usually pushing as hard as he can. It’s like an isometric exercise. Planchadores would probably do well in arm wrestling competitions.

Look at Nestor’s face in the photo below left. You can almost hear him grunt. The man is putting some serious effort into ironing the top of the hat, the plantilla.

Ironing the plantilla. Ironing the side (la copa).

The hot iron rests on a cloth as the

planchador

rubs more sulfur powder into the brim.

Nestor frequently puts the iron down momentarily as he rubs more sulfur powder into the hat.

Nestor Franco worked harder than any planchador I have ever watched and/or photographed. It is not a coincidence that his hats were the best-ironed of all.

Vaya con dios, Don Nestor.

Alvaro Franco. Nestor’s brother. Another great planchador. Another early death from alcohol. Liver cancer. 2005.

You too, Alvaro: Vaya con dios. At 4 feet 6 inches, you were always a big man in my eyes.

That’s Alvaro standing beside Trent Johnson of Greeley Hatworks. right

I liked Alvaro. Not so much when he would come to my hotel at 6 a.m. to sell me hats. I liked him more in the afternoon, when I watched him iron hats. He caused the Alvaro Rule. I put out the word that I would not buy from any dealer who came to or called my hotel. Good rule. It worked. I always visited every dealer, oldest friends first.

Twins, separated at birth.

Like Nestor, Alvaro was a great planchador. He practiced the family trade. He worked hard. His hats were beautifully ironed.

I didn’t realize how critically important the ironing is until the planchadores I knew passed away. I could see the decline in the quality of the work. The new ones proved to me that Nestor and Alvaro were artists.

The first ironing.

Above, the planchador is preparing hats for the first ironing. Some planchadores do the first ironing before the hats go to the apaleador. Some do the first ironing after the hats come back from the apaleador. This planchador uses a modern iron for the first ironing. For the “real” ironing, he uses an old iron just like Nestor and Alvaro used. You can see it hanging from a piece of rebar, below right.

Above left, the planchador stacks hats on forms after he has ironed the crowns. Above center, he melts candle wax onto the iron to keep it from sticking. Above right, he wipes each hat with sulfur powder several times during both the first and second ironing.

Above and below, the planchador uses a folded cloth to pick up his hot antique iron, then irons the brim and crown. This is the serious ironing. These hats have already been pounded by the apaleador and their straw edges have been trimmed more closely by the cortador.

A good planchador irons with the same kind of focus and intensity I remember seeing in Nestor and Alvaro many years ago. He must put his whole body into his ironing. After an hour of ironing, a good planchador is wet with sweat. Now that’s ironing! The good old fashioned way.

Ironing the hats is a critical part of the preparation. A good planchador does more than just iron. He must pull all the stretch out of the hats to establish and set the hat size. If the stretch is not taken out of the hats, the blocker (me) will have problems later.

Next you will see how I turn an unshaped hat into your favorite style of finished Panama hat.

|

The blocker shapes and styles the hats. Next Page |

|

15. The Blocker Shapes and Styles the Hats go to

Text and photos © 1988-2026, B. Brent Black. All rights reserved.

100% Secure Shopping