Featured In

About Us: Cigar Aficionado

There has always been a strong connection between Panama hats and good cigars.

Cigar Aficionado was kind enough to publish a lengthy article about my early work with the hats and the hat weavers in the Montecristi area.

The article originally appeared in the Summer 1993 issue. The text is reprinted below.

I have also included my photos which accompanied the text, plus some extras.

The title is: “On Top”

Subtitle: “A Montecristi is the best Panama hat but for how much longer?”

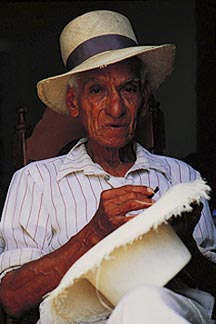

Sub-subtitle: “Two of the dwindling number of elderly hat weavers who make the world’s finest Panama hats, Montecristis.”

“Photography by Brent Black.” (I have included more photos than appeared with the article.)

In the town of Montecristi, Ecuador, the art of weaving Panama hats is slowly dying. Two generations ago, there were 2,000 weavers, but in the last generation the number dwindled to 200, and now there are only 20 master weavers left. A generation from now, because the current masters are in their 70s and 80s, there may be none. With the finest hats taking at least two months to finish and the best taking up to eight months, there is little time left to instruct young weavers in the art. Obviously, there is an irony in that what the world knows as a Panama hat actually comes from Ecuador. But the small, somewhat dreary coastal town of Montecristi has been for centuries a place where straw hats were woven. The difference is that the Montecristi Finos are simply the finest straw hats in the world, even to the point of defying the description straw. And with the makers dying off, the treasures of Montecristi are in danger of disappearing.

Brent Black, the former Associate Creative Director of Saatchi & Saatchi in San Francisco, isn’t about to let that happen. Eight years ago, he began an odyssey that eventually led to Montecristi, north of Guayaquil on the Pacific coast of Ecuador. What began as a passion to photograph the hats, soon turned into a mission to keep the hat making art alive. Black’s quest actually began in Mexico, in the Yucatán city of Mérida, where he read guidebook accounts of a crude Panama hat being woven in the region.

“It wasn’t easy,” says Black today. “I didn’t speak any Spanish, and even the shopkeepers and vendors who did speak a little English couldn’t understand what I wanted. No one knew what a Panama hat was. In Mérida, they call the hats jipijapas” (pronounced hee pee hop as). Through a shopkeeper, he finally photographed some weavers in a nearby town. But back in San Francisco, Black mentioned his hat search to someone at a cocktail party. An attorney familiar with Ecuador told him about the hats there—and specifically about Montecristis. The information triggered Black’s plunge into extensive research about the Panama hat and heightened his desire to see a Montecristi firsthand.

In 1988, he took off from his new base as Executive Creative Director of Ogilvy & Mather in Honolulu to fly to Guayaquil. From there, he boarded a series of brightly colored, sputtering buses and traveled one hundred miles up the coast to the city of Manta, a commercial fishing village, where he stayed overnight in the best hotel in town—at $2 a night. The next morning, he climbed aboard another bus to Montecristi. Before even getting off the bus, a nine-year-old boy appeared at his elbow. “Panama hat, meester. Panama hat, meester.”

“There aren’t too many gringo tourists in Montecristi,” laughs Black. “So when one does show up, he’s bound to attract a certain amount of attention. And there is no rational reason anyone would ever visit Montecristi except to buy hats.

“So, there I was. A four-foot-tall, self-appointed guide pulling at my shirt sleeve, a dog of rather questionable ancestry sniffing at my legs and before me lay the legendary town of Montecristi. To say the least, it wasn’t what I expected.

“I guess I had pictured in my mind a quaint, colorful little village with revered artisans working patiently in their workshops. The reality was quite different. Montecristi is rather drab.

The one—and two-story buildings are made mostly of wood and split bamboo, and they just blend into the dry, dusty hillside on which the town is built. Nothing colorful about them. Dogs and idlers lounge in whatever shade they can find. Children play in the streets and open areas. Pigs occasionally wander here and there. There are no hotels. No restaurants. The town only has running water a couple of hours each morning.

So, a little dismayed, I yielded to the tugging at my shirt sleeve and followed my guide up the hill.”

After a brief stop to meet 20 or so members of his guide’s family, Black went with the guide to the home/workshop/warehouse of the largest distributor of hats in Montecristi. It was a fairly substantial two-story building made of square red brick. A large two-inch-thick wooden door had been slid open to allow access to and provide light for the approximately 20 by 20-foot workshop. One man was working at finishing the weave on the edge of the brim of a hat, and a second was trimming the long ends of straws protruding from the inside of a hat. A dozen or so hat bodies in various stages of completion were stacked at their feet.

“I felt like I had stepped into a legend,” Black reflects. “There they were—Montecristi Finos. I had to actually pick one up and look at it closely to be able to see the pattern of the weave. That’s how finely woven they are.”

Black was introduced to the distributor. Conversation was difficult because Black spoke hardly any Spanish and the distributor didn’t speak English. With the help of a phrase book, a dictionary, pointing to objects and a lot of smiles, Black says he was able to communicate that he was interested in the hats and that he would be around for a week or so.

“It was, and is, very important to me,” Black’s earnestness comes through in the tone of his voice and the way he leans closer as he talks, “to do business the way it’s done in Latin America, not the way it’s done in the U.S. I didn’t want to blow into town, buy some hats and leave. That’s the way most gringos do business down there. I wanted to get to know them and for them to know me before any money changed hands.”

Black says the weavers were surprised when he pulled a chair over beside them and sat down. The distributor handed Black a stack of hats for his inspection and asked if he wanted to buy some. Black said yes, but not today. “Manana.” The distributor smiled, pulled his own chair over near Black and went back to counting and sorting hats.

Sitting among the weavers for most of the week, Black learned firsthand about the craft, the history and the legend of the Montecristi Fino hat. Occasionally, Black would carefully sort through hats offered to him, putting aside ones he eventually wanted to purchase. And he constantly asked if there were any even finer.

The weavers explained that the really, really fine hats are becoming rarer and rarer. They provided the estimate that there are maybe 20 master weavers left and shook their heads when asked if children were learning the trade. There’s a reason why this trade is dying: The work is hard. The finest hats are woven only at night, when it’s cooler, to protect the straw from being damaged by a weaver’s sweat, which might build up during the steamy equatorial days and stain the straw.

The weaving is done from a bent-over position, with the weaver’s chest resting on a small cushion on top of a wooden block and his arms extended down toward the floor, fingertips working on the fine straw. It’s a posture that is not just uncomfortable, it’s painful. The younger generation, if they weave at all, prefer to work on simpler pieces such as ladies’ handbags, fans and animal figures, which take less time and effort to complete.

“I suppose,” muses Black, “that the question is not so much why people might not want to weave bent over all night, as it is how they evolved the technique in the first place, and why they have practiced it for centuries. Sometimes I wonder if a really good industrial engineer could study the process and come up with some kind of jig or something that would allow the weavers to create traditional hats without having to weave in the traditional posture.”

Throughout the week, Black took photos of the weavers while they worked at finishing the edges and trimming straw from the hats. They warmed to him and took him out to other houses where other weavers were working.

“During that first incredible week, quite simply, I fell in love with the people, the hats, the weaving, the art form. And I became determined to do more than just buy a few dozen hats. I had found a mission. I wanted to preserve the art, to ensure that three generations from now the world will still be able to wear, admire and treasure Montecristi Finos.”

Since that first visit, Black has made numerous trips to Montecristi. He has become deeply involved with the weavers and the community. He often purchases large quantities of food to be distributed to the weavers and their families during times when weaving jobs are scarce and family incomes are down. He has taken some of the older weavers into Manta for prescription glasses. He sends Christmas presents every year. And, of course, everyone he photographs receives a copy of the picture. If you visited Montecristi, you would see Black’s photos in almost every house.

According to some of Black’s pamphlets on the subject of Panama hats, they are woven from various types of straw from all over the world: the Caribbean, Polynesia, the Philippines, Malaysia, China, Africa and on and on. Why have the straw hats woven in Ecuador risen to such an exalted position at the top of the hierarchy? One of the most important reasons is the straw itself.

The source of the straw is a kind of palm, known in scientific jargon as Carludovica palmata. In Ecuador the plant is called toquilla, the straw is called paja toquilla and the hats are called sombreros de paja toquilla. Although it has been found naturally as far north as Panama and as far south as Bolivia and has been successfully introduced into Mexico’s Yucatán peninsula, nowhere are conditions better for the plant’s growth than in the coastal lowlands of Ecuador.

The plants grow wild in abundance but could almost be said to be cultivated by those who “harvest” their straw. The unopened leaf chutes are cut from the plants with machetes. The green leaf casing is removed. The vein, spine and coarse edge are stripped away. Then, the opened, pale green palm fronds are put into 50-gallon oil drums filled with water. A fire under the drum boils the water. After an hour or so, the palm chutes are taken out of the water and hung up to dry on a clothesline. As they dry, the long strands shrink and curl lengthwise to form closed cylindrical fibers about a yard long. Each fiber is then slit into yet narrower strands, and the straw is boiled and dried again.

The straw is then ready for the weavers.

The hat weavers split the strands of straw to as fine a width as they are comfortable working with. The best weavers work with straw so fine that one has to look at the hat very closely to make out any weave pattern at all. “They’re incredible,” remarks Black. “The texture looks more like fine linen than straw.” The hats are woven from the center and worked out toward the edge of the brim. When the end of one strand of straw is reached, it is tied in a minute knot onto the next strand. This in turn forms little rings, or vueltas, inside the hats. Some claim that the number of rings inside a Montecristi directly relates to its quality. Black disagrees. He says that the number of rings, while sometimes a general indication of fineness of the straw, is not a reliable way to gauge the overall quality of the hat.

“It would be like counting the rings on a tree to decide how tall it is,” Black says. The metaphor is apt. At best, the number of rings may roughly correlate to the fineness of the straw. But if the straw is badly woven, with gaps or extra knots, then it is not a high-quality hat.

Black recommends the following criteria when selecting a Montecristi: the fineness and tightness of the weave; the evenness of the weave; the uniformity of color throughout; and the compact regularity of the “back weave”, the narrow band at the edge of the brim. “if you’re looking for a fine hat,” cautions Black, “never buy one with a brim that has been cut, folded under and sewn.” His anger boils over as he talks about what he almost considers a blasphemous affront to a handwoven hat. It is a shortcut often taken in finishing cheaper hats so that the brims all have the same width.

“The very finest hats will have—I don’t know quite how to describe it…” Black searches for the words. “They almost seem to glow. There is a kind of visual purity about them.” He laughs at his own passion about these hats. “To me, it’s almost as if they have an aura or halo around them.”

Weaving is not the only endangered art connected with hats. The practice of fine hand-blocking, or shaping, of the hats is also disappearing. “When I returned from Hawaii after that first trip, with a hundred or so Montecristi Finos, I had to find someone to block them. They were just hat bodies. Flat on top. Straight-walled, round crown. No leather sweatbands. No ribbons. Nothing. Without being blocked and finished, they were unmarketable.

“I began asking hat dealers in Hawaii and on the mainland. No one knew anyone who could do it for me. Pretty soon, I was making phone calls all over the country, following up on the thinnest of leads. Through a combination of persistence and luck, I finally found Michael Harris of Paul’s Hat Works in San Francisco.

“Michael is incredible,” says Black. “I think of him as the Sorcerer of Straw. He has the same reverence for the hats as I do. And he knows how to block and finish them so that their art is elevated, rather than compromised. He shapes them entirely by hand, one at a time, often employing tools that haven’t been made in decades and techniques that are all but lost or forgotten. When he’s finished, the hat is still just as soft and flexible as it was in Montecristi. There are only a handful of blockers left who can do that.”

It was critical to Black to have the integrity of the art extend all the way to the consumer. He didn’t use stiffeners or offer hats with the edges trimmed and sewn. He wanted to make sure that people would wear what the weavers had woven.

Today, Black distributes his Montecristi Finos through Kula Bay Tropical Clothing in Hawaii and Worth & Worth in New York. He insists on dealing with retailers who appreciate the level of workmanship and the sense of history of these fine Panamas. The completed hats sell for anywhere from $350 to $750 for a basic Montecristi to over $10,000 for a museum-quality piece. You can also buy hats at premium hat shops such as Paul’s Hat Works in San Francisco. There are several other grades of Panama hats that are more readily available to the buying public, and more affordable. Coarser weaves are found in most major cities of Ecuador, and even those hats have the telltale signature of true handwoven Panamas: the small, concentric circles woven outward from the center of the hat’s crown. These hats may take a weaver or several weavers just hours to complete. Interestingly, these Panamas often retain characteristics of weaving native to their regions. Cuenca, a town in the highlands south of Quito, is the home to a particularly handsome herringbone design that is somewhat tightly woven and intricate. The price for a more conventional straw hat varies from $50 to $110, and the best ones always retain some suppleness when handled.

Retailers who handle this kind of straw hat run the gamut and include Barneys, Neiman Marcus, Bigsby & Kruthers and J. Peterman; check locally with a major department store to see if it carries woven straw hats. Buyers should also beware of many claims by manufacturers that refer to their hats as genuine Montecristis when in fact they may be a lesser-grade Panama straw. Check with an expert hatter such as Paul’s Hat Works in San Francisco or Worth & Worth in New York for authentication. If you happen to be in Hawaii, genuine Montecristis also are sold by the Kula Bay Tropical Clothing outlets in several of the main hotels.

In the end, the buying public may be the determining factor for the future of Montecristis straw hats. “The only way to save this art is to create a demand for it,” explains Black. “Over the last few years, I’ve been able to purchase more Montecristi Finos than all other buyers combined. As a consequence, there are more weavers weaving now than at any time in the past twenty years. It’s working. We may actually be saving the art. But we have a long way to go.”

About a year ago, Black left Ogilvy & Mather to work full time on the hats. Besides day to day operations of importing, wholesaling and searching for additional retailers, Black sees his role as someone who is directly involved with the weavers, doing everything possible to encourage and reward their efforts.

He is in the initial stages of proposing the creation of a Panama hat museum, a project requiring the involvement of the Ecuadorian government. He feels that it is vitally necessary for the craftsmen to feel that their art is appreciated.

He also hopes to sponsor an annual contest which would award a substantial cash prize for the finest Montecristi. He sees this as a way to stimulate the weavers to strive for the highest levels of the art and to encourage young people to pursue the craft. He has already instituted a program to number and register each Montecristi Fino so that people who purchase a hat will be more conscious of the importance of what they own.

Most of all, Brent Black would like to see the public become aware of the talented artists who create these treasures and who struggle to pass their art on from one generation to the next. “Whenever someone purchases one of our Montecristi Finos, they are, in effect, commissioning another to be woven. It’s the only way these treasures will continue to exist.”

All photographs © B. Brent Black, except the Cigar Aficionado cover.

Text and photos © 1988-2026, B. Brent Black. All rights reserved.

100% Secure Shopping